Impact of GDPR on the Retention and Deletion of Chat Data

Businesses are increasingly focused on ensuring the protection of sensitive data. This is particularly true with regards to chat data, where maintaining privacy and security is of the utmost importance. In this context, the impact of GDPR regulations on the retention and deletion of such data is a critical issue that companies must address.

The proliferation of chat platforms across business functions—from customer service and sales to internal collaboration—has created a vast and complex ecosystem of conversational data. While invaluable for operational efficiency and customer engagement, this data presents a significant compliance challenge under the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the GDPR's impact on the retention and deletion of chat data, offering a comprehensive framework for legal, compliance, and IT professionals tasked with navigating this high-risk domain.

The report begins by deconstructing the foundational legal principles of the GDPR, primarily Article 5, which governs the entire data lifecycle. The principles of storage limitation, purpose limitation, and data minimisation are examined in detail, as they directly challenge the common organizational practice of retaining chat logs indefinitely. The analysis establishes that the unstructured, persistent, and often sensitive nature of chat data amplifies the compliance burden associated with these core tenets.

A critical component of this analysis is the establishment of a lawful basis for retaining chat data under Article 6. The report evaluates the suitability of consent, contractual necessity, legal obligation, and legitimate interests for various chat scenarios, highlighting the procedural complexities inherent in each. A key finding is that reliance on 'legitimate interests' for long-term retention creates a direct and often underestimated conflict with the data subject's 'right to erasure' under Article 17, requiring organizations to be prepared for active legal justification of their data retention policies.

The report then delves into the operational realities of data deletion, focusing on the powerful 'right to be forgotten'. It outlines the grounds for erasure, the critical exceptions, and the procedural best practices for handling data subject requests. Significant attention is given to the unresolved complexities of fulfilling erasure requests in multi-party conversations and the shortcomings of common technical solutions like pseudonymization, which often fail to meet the GDPR's high standard for true anonymization.

Furthermore, the analysis confronts the formidable technical and procedural hurdles to compliance. These include the near-impossibility of granularly deleting data from archival backups, the intricate retention settings of platforms like Microsoft Teams and Slack, and the common procedural failures—such as cumbersome request processes and inadequate identity verification—identified in case law from European data protection authorities. A central theme is the role of the accountability principle, which transforms internal technical debt and organizational inefficiencies into direct, punishable legal liabilities under the GDPR.

Finally, the report examines the severe financial and reputational risks of non-compliance, evidenced by multi-million Euro fines levied for data retention and processing violations. It looks to the future, exploring the new frontier of challenges posed by AI-powered chatbots. The "black box" nature of these systems fundamentally tests the GDPR's principles of transparency, purpose limitation, and the right to erasure, forcing a regulatory re-evaluation of these core concepts.

The report concludes with strategic recommendations centered on Data Protection by Design and Default, the mandatory use of Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) for high-risk systems, robust vendor management, and continuous organizational training. It is designed to serve as an authoritative guide for organizations seeking to build a defensible and sustainable compliance posture for their use of chat and messaging technologies.

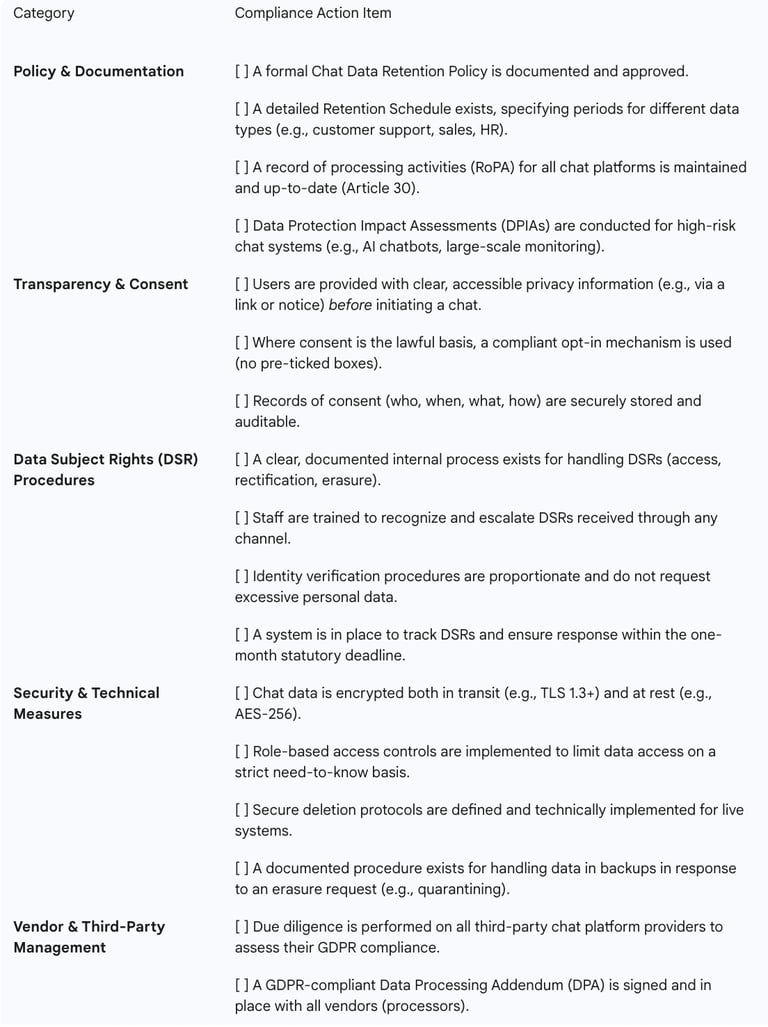

Table 1: GDPR Compliance Checklist for Chat Data Management

The GDPR Framework for Conversational Data

The General Data Protection Regulation establishes a comprehensive legal framework that governs the processing of personal data. For organizations utilizing chat and messaging platforms, understanding these foundational principles is not merely a matter of legal theory but a prerequisite for operational compliance. The principles outlined in Article 5 of the GDPR dictate the entire lifecycle of chat data, from its initial collection to its eventual deletion, and define the legal parameters within which all retention policies must operate.

1.1. The Foundational Pillars: Storage Limitation, Purpose Limitation, and Data Minimisation (Article 5)

Three principles from Article 5 are of paramount importance to the management of chat data: storage limitation, purpose limitation, and data minimisation. These principles form a triad that directly counters the tendency for digital data, particularly unstructured conversational data, to be retained indefinitely and used for purposes beyond its original context.

Storage Limitation (Art. 5(1)(e))

The principle of storage limitation is arguably the most direct challenge to traditional data hoarding practices. It mandates that personal data must be "kept in a form which permits identification of data subjects for no longer than is necessary for the purposes for which the personal data are processed". This principle fundamentally shifts the burden of proof onto the data controller. Instead of retaining data by default, an organization must be able to proactively justify the length of time it keeps every category of personal data it stores.

For chat data, this means that the common practice of storing chat logs indefinitely for "historical context" or "just in case" is presumptively non-compliant. Organizations are required to establish clear data retention periods and, once those periods expire, securely delete or anonymize the data. While the GDPR does not prescribe specific time limits, it requires that these periods be determined based on the necessity tied to the processing purpose. The regulation does permit longer storage periods for specific, narrow purposes such as "archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research purposes or statistical purposes," provided that appropriate safeguards under Article 89(1) are implemented.

Purpose Limitation (Art. 5(1)(b))

Closely linked to storage limitation is the principle of purpose limitation, which requires that personal data be "collected for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes and not further processed in a manner that is incompatible with those purposes". Before or at the time of collection, the data controller must clearly communicate these purposes to the data subject, typically through a privacy notice.

In the context of chat data, this principle has profound implications. For example, a chat transcript collected to resolve a customer's technical support issue has a specified purpose. Using that same transcript for an incompatible secondary purpose, such as training a new marketing AI model or analyzing customer sentiment for product development, would generally be prohibited without obtaining new, specific consent or establishing another valid lawful basis. The concept of "compatibility" is crucial; while some further processing may be deemed compatible, a significant deviation from the user's reasonable expectations at the time of data collection is likely to be considered a breach of this principle. The only explicit exceptions are for the same public interest archiving, research, or statistical purposes mentioned under storage limitation.

Data Minimisation (Art. 5(1)(c))

The principle of data minimisation requires that personal data be "adequate, relevant and limited to what is necessary in relation to the purposes for which they are processed". Organizations should collect only the personal data they truly need and should not collect data speculatively. For instance, a chatbot designed to facilitate newsletter sign-ups should only request the information necessary to send the newsletter, such as an email address, and should avoid gathering extraneous details like phone numbers or home addresses.

This principle is particularly challenging to apply to chat data. Unlike structured data entry forms where the controller can limit the fields, chat is a free-form, unstructured medium. Users may voluntarily provide excessive or even sensitive personal information that is not necessary for the stated purpose of the interaction. This places a significant onus on organizations to design their chat interfaces and train their agents or configure their chatbots to avoid soliciting unnecessary information and to have procedures for handling unsolicited data.

The inherent nature of chat data—unstructured, verbose, and often stored indefinitely by default—creates a unique compliance strain. GDPR principles were largely conceived with structured data in mind. When applied to the free-flowing, persistent nature of conversations, their demands are amplified. A single customer service chat can generate a data record containing far more personal information than necessary (challenging data minimisation), which is then stored by default for years (challenging storage limitation), and may contain details that tempt repurposing for analytics (challenging purpose limitation). This transforms chat from a simple communication channel into a high-risk data processing activity, where every interaction simultaneously implicates every core data protection principle.

1.2. Defining "Personal Data" in the Context of Chat Logs

To understand the full scope of the GDPR's impact, it is essential to appreciate the regulation's intentionally broad definition of "personal data." Article 4(1) defines it as "any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person". The term "identifiable" is key; it means a person who can be identified, directly or indirectly, through identifiers. This broad and deliberately vague definition is designed to be technology-neutral and future-proof, encompassing a wide range of information far beyond just a name or email address.

Chat logs are exceptionally rich sources of personal data, often containing multiple layers of identifiers:

Direct Identifiers: This is the most obvious category and includes information explicitly shared within the conversation that directly identifies an individual. Examples include full names, email addresses, phone numbers, account numbers, and physical addresses.

Online Identifiers and Metadata: Modern chat systems automatically collect a significant amount of data about the user and their device. This includes IP addresses, user agents (browser and operating system details), device IDs, cookie identifiers, and geolocation data. The GDPR's Recital 30 explicitly states that such online identifiers can "leave traces which, in particular when combined with unique identifiers and other information received by the servers, may be used to create profiles of the natural persons and identify them". Therefore, this metadata is unequivocally personal data.

Conversation Content: The transcript of the chat itself is personal data if it can be linked to an individual. The content can reveal biographical information, work history, family details, personal preferences, and opinions. Even information that appears anonymous in isolation, such as a user's political opinions shared on a forum, is considered personal data under the GDPR if it is linked to an account or identifier.

Special Category (Sensitive) Data: If a chat conversation reveals information concerning "racial or ethnic origin, political opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, or trade union membership," or contains "genetic data, biometric data for the purpose of uniquely identifying a natural person, data concerning health or data concerning a natural person's sex life or sexual orientation," it falls under the special categories of personal data defined in Article 9. Processing this type of data is prohibited unless one of a limited number of explicit conditions is met, such as explicit consent from the data subject. The unsolicited disclosure of such information by a user in a support chat places a significant compliance burden on the organization.

1.3. The Supporting GDPR Principles (Article 5)

While storage limitation, purpose limitation, and data minimisation are the most critical for retention and deletion, the other principles of Article 5 provide the essential context for compliant data handling.

Lawfulness, Fairness, and Transparency (Art. 5(1)(a)): Processing must have a lawful basis (discussed in Part II), and it must be fair and transparent. For chat, transparency means users must be clearly and concisely informed before the conversation begins about what data is being collected, for what purpose, how long it will be stored, and what their rights are. Hiding this information in lengthy legal documents or failing to provide it at the point of interaction violates this principle.

Accuracy (Art. 5(1)(d)): Organizations must take "every reasonable step" to ensure that personal data is accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date. Inaccurate data must be "erased or rectified without delay". This means organizations must have procedures in place to allow users to correct personal data contained within chat logs if a request is made.

Integrity and Confidentiality (Art. 5(1)(f)): Personal data must be processed in a manner that ensures its security, "including protection against unauthorised or unlawful processing and against accidental loss, destruction or damage". For chat data, this necessitates strong technical and organizational measures, such as end-to-end encryption for data in transit and encryption at rest for stored logs, as well as robust access controls to prevent unauthorized employee access.

Accountability (Art. 5(2)): The controller is not only responsible for complying with these principles but must also be "able to demonstrate compliance". This is the lynchpin principle that elevates GDPR compliance from a set of rules to a continuous program of governance. It requires comprehensive documentation of all data processing activities, policies, decisions (such as the reasoning behind a specific retention period), and procedures, creating an auditable trail for supervisory authorities.

Justifying Retention: Lawful Basis and Policy Formulation

The GDPR mandates that all processing of personal data, including its retention, must be grounded in a valid legal justification. Article 6 provides an exhaustive list of six "lawful bases" for processing. The choice of a lawful basis is a fundamental step that must be taken before processing begins, as it determines the scope of the data subject's rights and the controller's obligations. This section analyzes these lawful bases in the context of chat data retention and provides a structured approach to formulating a defensible retention policy.

2.1. Establishing a Lawful Basis for Retention (Article 6)

An organization must identify and document the most appropriate lawful basis for each distinct purpose for which it retains chat data. It is not possible to simply choose a basis that seems easiest; the choice must genuinely reflect the nature of the processing.

Consent (Art. 6(1)(a)): This basis is appropriate when the user is offered a genuine choice and control over their data. Consent must be a "freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication" of the data subject's wishes, signified by a clear affirmative action. For chat platforms, this means no pre-ticked boxes and a clear opt-in process. Consent is often the correct basis for retaining chat logs for marketing purposes or for non-essential chatbot functionalities. However, it is a fragile basis; the data subject has the right to withdraw consent at any time, and this withdrawal must be as easy as giving consent. Upon withdrawal, if there is no other overriding lawful basis, the data must be erased.

Performance of a Contract (Art. 6(1)(b)): This basis applies if retaining the chat data is necessary for the performance of a contract with the data subject, or to take steps at their request prior to entering into a contract. For example, retaining a chat transcript where a customer provided their address for a delivery is necessary to fulfill the purchase contract. The retention period under this basis is naturally linked to the lifecycle of the contract, including any warranty periods or timeframes for handling disputes.

Legal Obligation (Art. 6(1)(c)): This is a powerful basis that applies when the controller is required to retain data to comply with a specific law in the EU or a Member State to which they are subject. Examples include obligations under tax law to retain financial transaction records for a set number of years, or requirements in some jurisdictions to retain employee records. A court order mandating the preservation of chat logs for litigation would also fall under this basis. When this basis applies, it can override a data subject's right to erasure.

Vital Interests (Art. 6(1)(d)): This basis is extremely narrow and applies only when processing is necessary to protect someone's life. It is highly unlikely to be a relevant basis for the routine retention of chat data.

Public Task (Art. 6(1)(e)): This applies to processing necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority. It is primarily relevant for public authorities and is generally not applicable to private sector organizations' use of chat data.

Legitimate Interests (Art. 6(1)(f)): This is the most flexible but also the most challenging basis. It can be used when processing is necessary for the legitimate interests pursued by the controller or a third party, except where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject. To rely on this basis, the controller must conduct and document a three-part balancing test, often called a Legitimate Interests Assessment (LIA) :

Purpose Test: Identify a legitimate interest (e.g., preventing fraud, ensuring network security, improving customer service, internal training).

Necessity Test: Show that retaining the chat data is necessary to achieve that interest.

Balancing Test: Weigh the controller's interests against the individual's rights and freedoms. This requires considering the nature of the data, the user's reasonable expectations, and the potential impact on the individual.

Legitimate interests are often the most plausible basis for retaining customer support chats for quality assurance or internal employee chats on platforms like Slack or Teams for business continuity. However, this choice carries significant procedural implications.

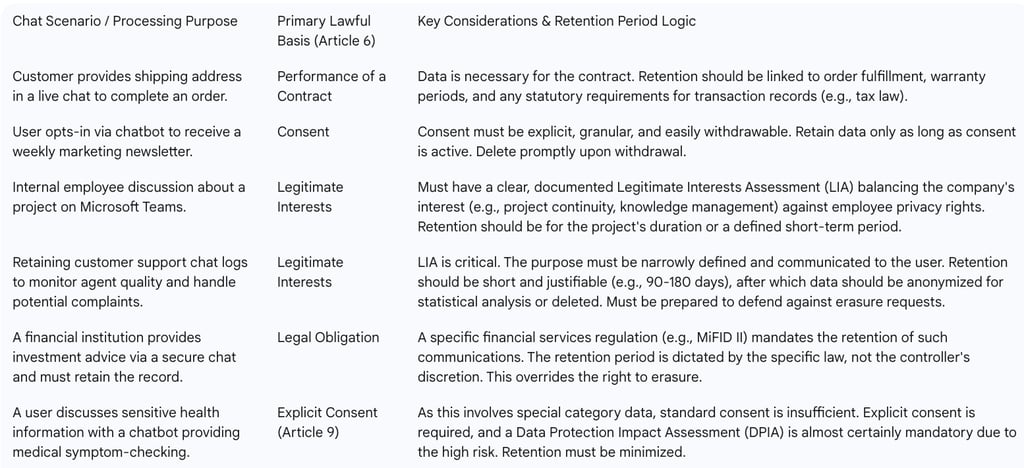

Table 2: Mapping Lawful Basis to Chat Data Processing Purpose

The choice of 'legitimate interests' as a basis for retaining chat data, particularly for longer periods, creates a direct and unavoidable tension with the data subject's rights. Consider an organization that retains a support chat log for three years under the legitimate interest of defending against potential future legal claims, a period aligned with a common statute of limitations. If the customer exercises their right to erasure under Article 17 after six months, the organization must refuse the request. To do so, it must demonstrate that its interest constitutes an "overriding legitimate ground" or falls under the specific exemption for the "establishment, exercise or defence of legal claims". This requires a direct communication to the customer explaining the refusal, which can easily escalate into a dispute or a formal complaint to a Data Protection Authority (DPA). The DPA would then likely scrutinize the original LIA and the proportionality of the three-year retention period. This transforms what was intended as a passive data storage policy into a potentially active and contentious legal process, imposing a significant operational and legal overhead that organizations frequently underestimate.

2.2. Crafting a GDPR-Compliant Chat Data Retention Policy

A formal, documented data retention policy is not merely a best practice; it is a core requirement of the accountability principle. This policy should be a clear, authoritative document that governs how chat data is managed throughout its lifecycle.

The development process should follow a structured methodology:

Assign Responsibility: A cross-functional team comprising representatives from Legal, IT/Security, and relevant business units (e.g., Customer Service, HR) should be tasked with creating and maintaining the policy. This ensures all perspectives and requirements are considered.

Data Audit & Mapping: The first step is to create a comprehensive inventory of all chat platforms used within the organization (e.g., website live chat, internal messaging, chatbots). For each platform, the team must map the types of personal data collected, where it is stored, how it flows between systems, and who has access.

Define Purpose & Lawful Basis: For each category of chat data identified, the policy must explicitly state the specific purpose of its retention and the corresponding lawful basis from Article 6. This documentation is crucial for demonstrating compliance to regulators.

Create a Retention Schedule: This is the operational core of the policy. A retention schedule is a detailed document or table that specifies the exact retention period for different classes of records. For example, it might state: "Customer support chat transcripts: Retain for 90 days from chat conclusion, then securely delete," or "Internal HR-related chat messages: Retain for 7 years post-employment termination."

Define Deletion/Anonymization Protocols: The policy must specify the technical methods for how data will be disposed of once its retention period expires. This should detail the standards for secure erasure to ensure data is irrecoverable, or the methodology for anonymization if the data is to be retained for statistical purposes.

Review and Update: The regulatory and business landscape is dynamic. The retention policy must be a living document, subject to regular review (at least annually) and updated whenever new chat systems are introduced, business processes change, or relevant laws are amended.

2.3. Determining Defensible Retention Periods

The GDPR's principle of storage limitation does not provide fixed time limits, stating only that data should be kept for "no longer than is necessary". Determining what is "necessary" is a risk-based decision that the controller must make and be able to defend. A defensible retention period is based on a clear rationale derived from one of the following sources:

Statutory Requirements: The most straightforward justification is a legal or regulatory requirement. Many jurisdictions have laws mandating the retention of certain types of records, such as financial transaction data for 6-7 years for tax purposes or specific employment records. The French DPA, CNIL, provides concrete examples, such as a 5-year retention for payroll data or 6 months for security log data, which can serve as benchmarks.

Contractual Necessity: The retention period can be tied to the duration of a contract and any subsequent period required to handle warranty claims, returns, or potential contractual disputes. For example, data related to a product sale might be retained for the length of the product's warranty plus a reasonable period for claims to be filed.

Business Purpose (under Legitimate Interests): This requires the most careful justification. The period must be the minimum reasonable time needed to achieve the defined purpose. For instance, retaining support chats for 90 days to conduct quality reviews and provide agent feedback is a specific, time-bound purpose. Retaining sales-related chats for a period like 18 months, as some platforms do, might be justified based on the average length of a sales cycle, after which the lead is considered dormant. Any period chosen under this basis must be documented and justified in an LIA.

User Expectations: A crucial, albeit less formal, consideration is what a data subject would reasonably expect. A user engaging in a quick, transactional chat with a bot would likely not expect that conversation to be stored for several years. Aligning retention periods with user expectations can reduce the risk of complaints and enhance trust.

Ultimately, setting retention periods is a balancing act between business needs, legal obligations, and data subject rights. Arbitrary periods are indefensible; every timeframe in the retention schedule must be linked back to a specific, documented purpose and lawful basis.

The Obligation to Forget: Deletion and the Right to Erasure

The GDPR enshrines one of the most powerful rights for data subjects: the right to have their personal data deleted. Formally known as the 'right to erasure' and popularly as the 'right to be forgotten', Article 17 places a clear obligation on data controllers to erase personal data under specific circumstances. For chat data, which is often personal and persistent, this right presents significant operational challenges, from interpreting the grounds for erasure to navigating the complexities of multi-party conversations.

3.1. The Right to Erasure (Article 17) in Context

The right to erasure is not an absolute right to have data deleted on demand. It is triggered only when one of several specific grounds applies. Organizations must have a clear understanding of these grounds to correctly assess the validity of an erasure request.

Grounds for Erasure

According to Article 17(1), a data subject has the right to obtain erasure of their personal data "without undue delay" when one of the following applies :

Data is No Longer Necessary: The personal data is no longer needed for the purpose for which it was originally collected or processed. This directly links to the principles of purpose limitation and storage limitation. Once a retention period expires, this ground is automatically met.

Withdrawal of Consent: The processing is based on consent (under Article 6(1)(a) or 9(2)(a)), and the data subject withdraws that consent. If there is no other legal ground for the processing, erasure is mandatory.

Objection to Processing: The data subject objects to the processing based on legitimate interests (Article 21(1)), and the controller cannot demonstrate "overriding legitimate grounds" for the processing. The right to object is absolute in the case of direct marketing (Article 21(2)).

Unlawful Processing: The personal data has been processed unlawfully, for example, without a valid lawful basis in the first place.

Compliance with a Legal Obligation: Erasure is necessary for the controller to comply with a legal obligation under EU or Member State law.

Data Collected from a Child: The data was collected in relation to the offer of information society services to a child (under Article 8(1)).

Critical Exceptions

Article 17(3) provides several key exceptions where the obligation to erase does not apply. These are crucial for organizations handling chat data, as they provide grounds for legitimately refusing a request. The most relevant exceptions include processing that is necessary for:

Exercising the right of freedom of expression and information: This is a high-threshold exception, typically relevant for journalistic, academic, artistic, or literary purposes, and is less likely to apply to standard commercial chat data.

Compliance with a legal obligation: If a separate law requires the organization to retain the data (e.g., anti-money laundering regulations requiring retention of customer communications), this obligation overrides the right to erasure.

Archiving in the public interest, scientific or historical research, or statistical purposes: This applies where erasure would likely "render impossible or seriously impair the achievement of the objectives of that processing".

The establishment, exercise or defence of legal claims: This is a highly significant exception. An organization can refuse to delete chat data if it is reasonably necessary to retain it to defend against a potential lawsuit or to establish its own legal claim. For example, a chat log containing a customer's agreement to terms of service could be retained for the duration of the relevant statute of limitations.

3.2. Fulfilling Erasure Requests: Procedural Best Practices

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) has observed that many GDPR infringements related to erasure are not due to a refusal to delete, but to procedural and organizational failures. A robust, well-documented internal process for handling Data Subject Requests (DSRs) is therefore essential for compliance.

The process should include the following stages:

Intake and Verification: Staff must be trained to recognize an erasure request, which can be made verbally or in writing and does not need to use specific legal terminology. The organization must then verify the identity of the requester. This step is a common failure point; the EDPB has criticized controllers for demanding excessive information, such as a copy of a national ID card, by default, which violates the data minimisation principle. Verification should be proportionate, using information already held by the controller where possible (e.g., sending a verification link to the registered email address).

Triage and Assessment: Once a request is verified, it must be assessed against the grounds and exceptions in Article 17. The legal and compliance teams should determine if a valid ground for erasure applies and if any exemptions justify refusal. This assessment and its outcome must be documented.

Execution: If the request is valid, the data must be securely deleted from all live systems. A critical part of this step is the obligation under Article 19 to communicate the erasure to any third parties to whom the data was disclosed (e.g., a CRM provider integrated with the chat platform), unless doing so proves impossible or involves disproportionate effort.

Communication: The controller must respond to the data subject "without undue delay" and, at the latest, within one month of receiving the request. This response must either confirm that the data has been erased or, if the request is refused, clearly explain the reasons for the refusal and inform the individual of their right to lodge a complaint with a DPA and to seek a judicial remedy. Failure to communicate the outcome is a common infringement noted in EDPB case law.

3.3. The 'Right to be Forgotten' in Multi-Party Conversations

The application of the right to erasure to multi-party conversations, such as group chats or even two-person dialogues, creates a significant legal and practical dilemma. When one user requests the deletion of a conversation, it directly implicates the personal data of all other participants in that conversation. The GDPR does not provide a clear hierarchy of rights to resolve this conflict, pitting one user's right to erasure against another's right of access (Article 15) or their interest in retaining a complete record of their communications.

Organizations and platforms have adopted various approaches to this problem, each with its own compliance risks:

Deletion for All: Deleting the conversation or specific messages for all participants fully honors the requester's right but may infringe on the rights of other participants who wish to retain the record.

Deletion for Requester Only: The platform removes the conversation from the requester's view but leaves it intact for other participants. While technically simpler, this approach may not constitute true "erasure" under the GDPR, as the data still exists on the controller's servers.

Anonymization/Pseudonymization: A common technical compromise is to replace the requester's name and other direct identifiers with a generic placeholder like "" while leaving the message content intact.

This latter approach, while appealing, often creates a hidden compliance gap. The GDPR sets an extremely high bar for anonymization: the data must be rendered irreversibly non-identifiable by any means "reasonably likely to be used". Simply replacing a username is typically pseudonymization, not anonymization, because the data can often be re-identified using additional information. Pseudonymous data remains personal data under the GDPR. The content of the messages themselves ("I'm the marketing director at Acme Inc. and my direct line is...") can easily serve to re-identify the individual, even without their name attached. True anonymization would require redacting the message content, a process that is technically complex, may destroy the contextual value of the log for other participants, and could be viewed as a form of censorship. Therefore, what many platforms implement as a compliant "anonymization" feature does not, in fact, fully satisfy an Article 17 erasure request, leaving the controller exposed to legal risk.

Navigating the Technical and Procedural Minefield

Translating the GDPR's legal requirements for chat data retention and deletion into practice is fraught with technical and procedural challenges. The realities of modern IT infrastructure, the design of communication platforms, and the fallibility of internal processes can create significant gaps between policy and execution. This section explores these on-the-ground challenges, from the intractable problem of backups to the specific hurdles posed by popular platforms and the common procedural failures that lead to non-compliance.

4.1. The Challenge of Backups and Archives

One of the most daunting technical challenges in fulfilling an erasure request is the requirement to delete data from all systems where it is stored, which includes backup and archival systems. While deleting a user's record from a live, production database is often straightforward, the same cannot be said for backups.

The core problem lies in the architecture of most backup systems. They are often designed for bulk recovery and data integrity, not for granular, surgical deletion. Backups may be stored as large, compressed, and immutable files, or written sequentially to media like magnetic tapes. Attempting to restore a massive backup file, locate and delete a single user's chat data, and then re-archive the file is not only technically complex and resource-intensive but also risks corrupting the integrity of the entire backup, rendering it useless for its primary purpose of disaster recovery.

Recognizing this technical infeasibility, data protection authorities have developed a pragmatic, risk-based approach:

Immediate Erasure from Live Systems: The primary obligation is to delete the personal data from all active, production environments as soon as the request is validated.

Isolate and Quarantine Backup Data: The data within the backup systems must be effectively put "beyond use". This means implementing technical and organizational controls to ensure that this data is not accessed for any purpose and will not be restored to a live environment.

Log the Erasure Request: The organization must maintain a secure log of all data that has been subject to a valid erasure request but still exists in backups. This log is essential for accountability.

Delete Upon Restoration: If a backup containing the flagged data ever needs to be restored, the organization has an obligation to consult the log and delete the relevant personal data as part of the restoration process, before the system goes live.

Transparency with the Data Subject: The organization should be transparent with the individual, informing them that their data has been erased from live systems but may persist in backup archives for a limited, defined period until the backup media is overwritten as part of the normal lifecycle.

This approach creates a state of "latent non-compliance," where the data technically still exists in a non-production environment. This risk is generally considered acceptable by regulators, provided the organization has robust controls, a clear policy, and minimizes the retention period of the backups themselves.

4.2. Platform-Specific Hurdles and Solutions

Different types of chat platforms present unique challenges and offer varying levels of control for implementing GDPR-compliant retention and deletion policies. The data controller (the organization using the platform) remains ultimately responsible for compliance, regardless of the platform's native features.

Internal Messaging Systems (Microsoft Teams, Slack)

These platforms have become central to internal business communication, but their default settings are often geared towards indefinite retention for the sake of preserving corporate knowledge.

Microsoft Teams: Microsoft provides administrators with granular retention policies through its Purview compliance portal. Admins can configure policies to retain data, delete data, or retain for a specific period and then delete. A significant hurdle is that these policies can create a disconnect between the user's experience and the actual state of the data. A user might "delete" a message from their view, but if an administrative retention policy is in place, a copy is preserved in a secured location for eDiscovery purposes. Fulfilling an erasure request therefore requires administrative action, not just user action. Historically, the inability for end-users to delete entire chat threads has been a point of contention and a potential GDPR violation, leading platforms to slowly introduce such features under regulatory pressure.

Slack: Slack also provides compliance features, including tools for data export and profile deletion, which are essential for responding to DSRs. Organizations can set custom retention policies to automatically delete messages and files after a specified period. However, the organization, as the data controller, is responsible for configuring these settings correctly and understanding their implications. For instance, a basic profile deletion might not erase all messages sent by that user in channels that are themselves subject to a separate retention policy.

Customer Service Platforms (Zendesk, Intercom, etc.)

These platforms are designed to create and maintain a persistent record of customer interactions to provide context for support agents. This design goal is in direct tension with the principle of storage limitation.

Most reputable providers of these platforms are aware of their GDPR obligations as data processors and offer features to assist their customers (the data controllers) with compliance. This typically includes APIs or user interface tools to search for and delete customer data, manage consent, and configure data retention settings.

The critical responsibility for the organization is to perform due diligence on the vendor, ensure a comprehensive Data Processing Addendum (DPA) is in place, and correctly configure the platform's retention and deletion settings to align with its own data retention policy. Simply using a "GDPR-compliant" platform does not absolve the controller of its accountability.

4.3. Procedural Failures and How to Avoid Them: Lessons from EDPB Case Law

The EDPB's analysis of decided cases across the EU provides invaluable insight into the common procedural pitfalls that lead to GDPR violations in handling erasure and objection requests. These failures are often not malicious but stem from inadequate processes and technical shortcomings.

Common procedural failures include:

Overly Cumbersome Procedures: Forcing data subjects to navigate complex web forms, use specific channels when the request was made through another, or providing contact email addresses that are unmonitored or return automated responses that redirect the user elsewhere. The process must be straightforward.

Excessive Identity Verification: As previously noted, demanding disproportionate proof of identity, such as a passport copy for a simple newsletter unsubscribe, is a violation of data minimisation and can be seen as a tactic to discourage requests.

Poor Internal Processes: The most frequent source of failure is poor internal organization. Requests are not forwarded to the correct department, are misclassified by untrained staff, or are simply lost due to a lack of a centralized tracking system for DSRs.

Technical Deficiencies: Legacy systems are often a root cause of non-compliance. In some cases, data was stored in a way that made deletion technically difficult (e.g., as unauthenticated URL links). In others, the "delete" function in a system merely flagged a record as inactive rather than performing a true, permanent erasure from the database.

Lack of Communication: A significant number of infringements involve the controller successfully deleting the data but failing to inform the data subject that the action has been completed within the one-month statutory timeframe.

These recurring failures highlight a crucial aspect of GDPR compliance. The accountability principle, as outlined in Article 5(2), requires controllers to be both responsible for and able to demonstrate their compliance. This means that internal failings, such as outdated IT systems, poor inter-departmental communication, or inadequate staff training—often categorized as "technical debt" or "organizational debt"—are not valid excuses for failing to fulfill a data subject's rights. The GDPR effectively transforms this internal operational debt into a direct, punishable legal liability. An organization's inability to delete data because its systems are not designed for it is not a defense; it is, in itself, evidence of a failure to implement Data Protection by Design and a breach of the accountability principle. This underscores that investing in modern data governance systems and streamlined DSR workflows is not merely an operational improvement but a core legal risk mitigation strategy.

Enforcement, Risk Mitigation, and Future Outlook

Understanding the legal, technical, and procedural aspects of chat data management under the GDPR is incomplete without considering the consequences of failure and the evolving challenges on the horizon. The enforcement powers of data protection authorities are substantial, and the rapid advancement of technologies like AI chatbots is introducing new layers of complexity that test the very foundations of data protection law. Proactive risk mitigation is therefore not just advisable but essential for sustainable compliance.

5.1. The Cost of Non-Compliance: Enforcement and Penalties

Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) across the EU are empowered with a range of corrective measures to address GDPR infringements. These powers are not limited to financial penalties and can have significant operational impacts.

Corrective Powers: DPAs can issue warnings and reprimands for likely or minor infringements. For more serious violations, they can impose a temporary or definitive ban on processing activities, effectively halting a business's ability to use chat data. They can also order the controller to bring processing operations into compliance, which may involve rectifying or erasing data.

Administrative Fines (Article 83): The GDPR is renowned for its two-tiered system of administrative fines, which are designed to be "effective, proportionate and dissuasive".

Lower Tier: Infringements of obligations related to technical and organizational measures, such as those for processors, breach notifications, and DPIAs, can result in fines of up to €10 million or 2% of the undertaking's total worldwide annual turnover of the preceding financial year, whichever is higher.

Higher Tier: Violations of the core data processing principles in Article 5 (including purpose and storage limitation), the conditions for consent, the rights of data subjects (including the right to erasure), and rules on international data transfers are subject to fines of up to €20 million or 4% of total worldwide annual turnover, whichever is higher.

When deciding on a fine, authorities consider numerous factors, including the nature, gravity, and duration of the infringement; its intentional or negligent character; actions taken to mitigate damage; and the degree of cooperation. Real-world enforcement actions have demonstrated regulators' willingness to impose substantial penalties. While many of the largest fines have focused on the legal basis for advertising (Meta, Amazon), they often cite failures in fundamental principles like lawfulness, transparency, and purpose limitation, which are directly relevant to chat data retention. A notable example is the €32 million fine issued by the French CNIL against Amazon France Logistique for, among other things, excessively intrusive employee monitoring and retaining the resulting data for longer than necessary, a direct violation of the storage limitation principle.

5.2. The New Frontier: GDPR and AI Chatbots

The rapid proliferation of sophisticated, generative AI-powered chatbots represents the most significant emerging challenge to the application of GDPR principles to conversational data. These systems introduce complexities that the drafters of the regulation could not have fully anticipated.

Heightened Transparency Challenges: Article 13 and 14 of the GDPR require controllers to provide data subjects with "meaningful information about the logic involved" in automated decision-making. Explaining the inner workings of a complex, probabilistic Large Language Model (LLM) in a way that is "concise, transparent, intelligible and easily accessible" is exceptionally difficult, if not impossible. This creates a fundamental tension with the transparency principle.

Purpose Limitation and Model Training: A primary use of conversational data in the AI context is to train or fine-tune the underlying model. This constitutes a new processing purpose. Using customer support chat data to train a global AI model is likely incompatible with the original purpose of resolving a specific query. This requires a separate, valid lawful basis. While some developers may attempt to rely on 'legitimate interests', this is a contentious area currently under intense scrutiny by regulators like the EDPB and the ICO.

Data Minimisation vs. Big Data: The very paradigm of modern machine learning is that model performance improves with the volume and variety of training data. This is in direct philosophical and practical conflict with the GDPR's principle of data minimisation, which demands that only necessary data be processed.

The "Black Box" Problem and Erasure: The right to erasure faces a potentially insurmountable technical hurdle with AI models. If a user's chat data has been ingested and used to adjust the millions or billions of statistical parameters (weights) in an LLM, it is not possible to surgically remove the "influence" of that specific data. The model cannot simply "unlearn" it. This challenges the very concept of erasure. Recognizing this difficulty, regulators like the French CNIL have begun to explore alternative solutions, suggesting that where direct erasure from a model is infeasible, measures like filtering outputs to prevent the regurgitation of the user's data may be an acceptable, though indirect, way of respecting the right.

The advent of advanced AI chatbots is not just another technical challenge for GDPR compliance; it is a development that is actively forcing a regulatory re-evaluation of the core principles themselves. The GDPR was designed to be technology-neutral, but its framework was built upon an understanding of deterministic data processing. The probabilistic nature of generative AI challenges the foundations of transparency, purpose limitation, and erasure. The ongoing work of the European Parliament, the EDPB, and national DPAs shows that regulators are grappling with how to apply these "vague and open-ended" prescriptions to this new reality. Organizations operating at this intersection are not merely complying with existing law; they are participating in the evolution and future interpretation of data protection regulation itself.

5.3. Strategic Recommendations for Proactive Compliance

Given the legal risks and technical complexities, a reactive approach to GDPR compliance for chat data is untenable. Organizations must adopt a proactive, strategic posture grounded in the following pillars:

Data Protection by Design and Default (Article 25): This principle must be the starting point. When procuring a new chat platform or developing an in-house solution, privacy and data protection requirements must be embedded from the outset. This includes selecting platforms that offer granular retention controls, robust security features (like end-to-end encryption), and user-friendly tools for facilitating DSRs. The default settings of any chat system should be the most privacy-protective (e.g., shortest retention period, data collection minimized).

Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) (Article 35): A DPIA is a mandatory risk assessment for any data processing that is "likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons". The deployment of a new large-scale chat system, particularly one involving employee monitoring or the use of novel AI technology, will almost certainly trigger the requirement to conduct a DPIA. This process helps to identify and mitigate risks before the system goes live.

Robust Vendor Management: When using third-party chat platforms, the organization acts as the data controller and the vendor as the data processor. Thorough due diligence is essential. A comprehensive, GDPR-compliant Data Processing Addendum (DPA) must be in place. This DPA should contractually obligate the vendor to adhere to the controller's instructions regarding data retention, to implement specific security measures, to assist with DSRs, and to securely delete data at the end of the service contract.

Continuous Training and Auditing: GDPR compliance is an ongoing process, not a one-time project. Employees who use chat systems—from customer service agents to internal staff—must receive regular training on the organization's data retention policy, security protocols, and their role in identifying and handling DSRs. Periodic internal audits should be conducted to verify that policies are being followed in practice and to identify any new or unmanaged chat data streams.

Conclusion

The General Data Protection Regulation has fundamentally reshaped the landscape of data management, and its impact on the retention and deletion of chat data is particularly profound. The principles of storage limitation, purpose limitation, and data minimisation create a stringent framework that stands in stark opposition to the technical and cultural inertia that often leads to the indefinite retention of conversational data. For organizations, navigating this landscape requires a paradigm shift from passive data storage to active, justifiable data lifecycle management.

Compliance demands a multi-faceted strategy that begins with a solid legal foundation: identifying a valid lawful basis for each processing purpose and embedding this rationale within a comprehensive, documented data retention policy and schedule. This policy cannot be a static document; it must be a dynamic tool that guides operational decisions and is regularly reviewed to reflect evolving legal and business requirements.

The powerful rights granted to data subjects, especially the right to erasure, introduce significant operational complexity. Fulfilling these rights requires not only well-defined internal procedures for handling requests but also technical solutions capable of executing them effectively across live systems, archives, and third-party platforms. The challenges are substantial, from the technical infeasibility of granular deletion from backups to the unresolved legal questions surrounding multi-party conversations. As evidenced by regulatory enforcement actions, procedural failures born from inadequate systems or poor training are not considered valid excuses but are themselves breaches of the core accountability principle.

Looking forward, the rise of AI-powered chatbots presents the next frontier of compliance challenges, testing the limits of GDPR's foundational concepts of transparency, purpose, and erasure. Organizations venturing into this space must proceed with extreme caution, prioritizing Data Protection by Design and conducting rigorous risk assessments.

Ultimately, achieving and maintaining GDPR compliance for chat data is not merely a legal or technical task but a continuous program of organizational governance. It requires a proactive commitment to transparency, a disciplined approach to data minimisation, and a robust framework for managing the entire data lifecycle. By embracing these principles, organizations can not only mitigate significant legal and financial risks but also build deeper trust with the customers and employees who engage with them through these increasingly vital communication channels.